Decoding Henri Matisse

The legendary French artist Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) is widely regarded as the greatest colorist of the 20th century. He had every intention of becoming a lawyer, until that fateful day in 1889, when his mother brought him art supplies to play. It was that moment when he discovered ‘a kind of paradise’. Following his passion, in 1891 at the age of twenty-two he joined the Academie Julian in Paris to study art.

He was born in Le Cateau – Cambresis, France. He grew up in Bohain en Vermandois, Picardy, France where his parents owned a flower business. Matisse was a printmaker, a sculptor, a draughtsman but mainly was known as a painter. He is regarded along with Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in 20th century. He was an upholder of the classical tradition in French painting. In fact, his mastery of the expressive language of colour and drawing, displayed in a body of work spanning over a half-century, he was recognised as a leading figure in modern art.

He emerged as a Post – Impressionist and first achieved prominence as the leader of the French movement Fauvism. Although he was interested in Cubism, he rejected it, and insteas sought to use color as the foundation for expressive, decorative and monumental paintings.

Matisse was heavily influenced by art from other cultures. Having seen several exhibitions of Asian art, and having traveled to North Africa, he incorporated some of the decorative qualities of Islamic art, the angularity of African sculpture, and the flatness of Japanese prints into his own style. Chardin was one of Matisse’s most admired painters; as an art student he made copies of four Chardin paintings in the Louvre.

He used pure colors and the white of exposed canvas to create a light – filled atmosphere in his Fauve paintings. Matisse used contrasting areas of pure, unmodulated color where he followed these ideas throughout his ideas.

The human figure was mainly the central to Matisse’s work both in sculpture and painting. Some of his work reflects the mood and personality of his models, but more often he used them merely as vehicles for his own feelings, reducing them to ciphers in his monumental designs.

In 1896, Matisse visited the Australian painters John Russell off the coast of Brittany. Russell was the one who introduced him to Impressionism and to paintings of Vincent van Gogh. Since then Matisse’s style changed completely, abandoning his earth coloured palette for bright colours.

In 1898, he went to London to study the paintings of J.M.W. Turner. When he returned to Paris in 1899 he worked beside Albert Marquet and met Andre Derain, Jean Puy and Jules Flandrin.

Many of Matisse’s paintings from 1898 to 1901 make use of a Divisionist technique he adopted after reading Pail Signa’s essay, ‘Eugene Delacroix and Neo -impressionisme’.

Matisse died of a heart attack at the age of 84 in 1954. He is interred in the cemetery of the Monastere Notre Dame de Cimiez, near Nice. Thanks to the influence he had on painting following the 2nd World War, Henri Matisse’s reputation is higher than it has ever been before. He is an influential figure of the 2oth century and a decisive figure of the time where he had a great impact on future movements, and works produced by artists in the 20th century.

”What I dream of is an art of balance, purity, and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter… a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue. ”

– Henri Matisse

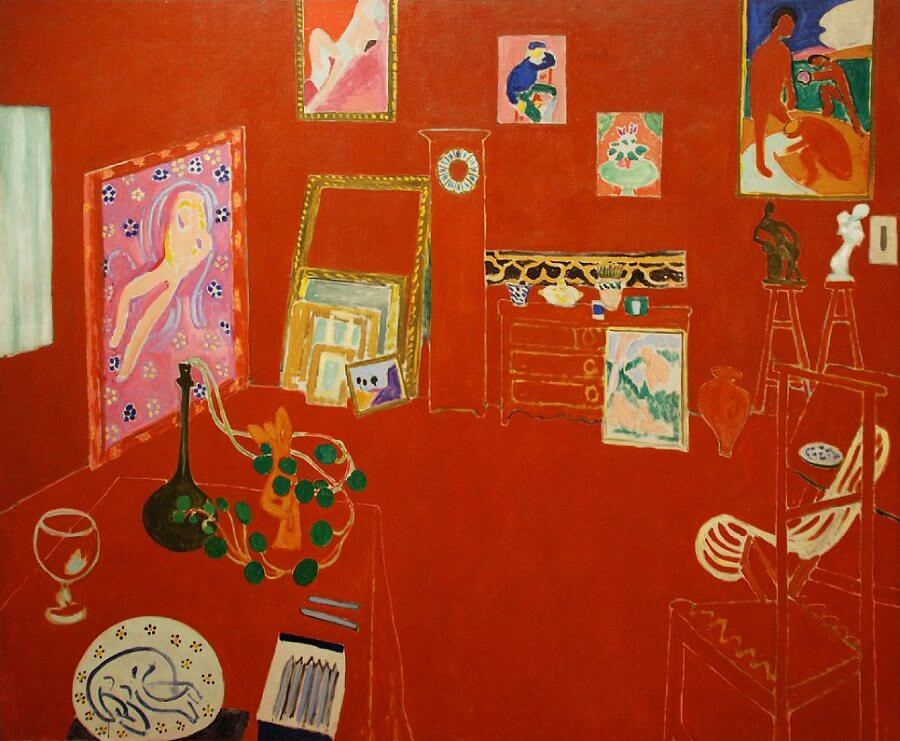

L’ Atelier Rouge, 1911

L’Atelier Rouge / The Red Studio – Features a small retrospective of Matisse’s recent painting, sculpture, and ceramics, displayed in his studio. The artworks appear in color and in detail, while the room’s architecture and furnishings are indicated only by negative gaps in the red surface. The composition’s central axis is a grandfather clock without hands – it is as if, in the oasis of the artist’s studio, time were suspended.

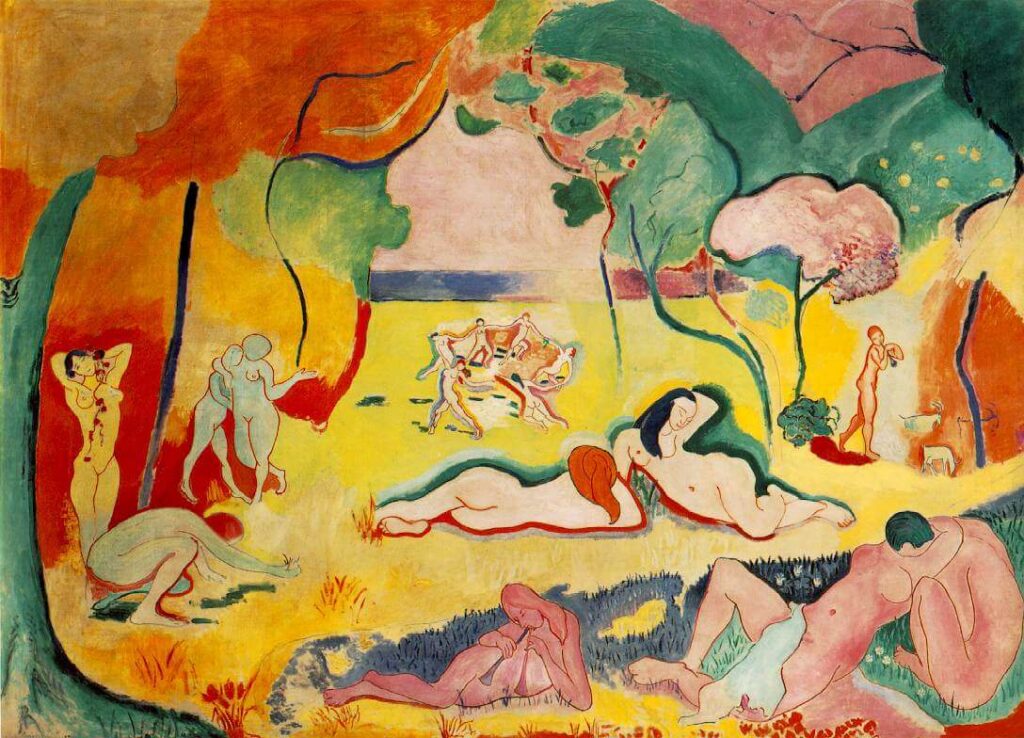

Joy of Life

Joy of Life is a large-scale painting (nearly 6 feet in height, 8 feet in width), depicting an Arcadian landscape filled with brilliantly colored forest, meadow, sea, and sky and populated by nude figures both at rest and in motion. As with the earlier Fauve canvases, color is responsive only to emotional expression and the formal needs of the canvas, not the realities of nature.

Sorrow of the King

The Sorrows of the King was Matisse’s final self portrait. This work refers to one of Rembrandt’s paintings, David Playing the Harp before Saul, in which the young biblical hero plays to distract the king from his melancholy, as well as to Rembrandt’s late self portraits. Here Matisse depicts the themes of old age, of looking back towards earlier life (La vie antérieure, the title of a poem by Baudelaire that Matisse had already illustrated) and of music soothing all cares.

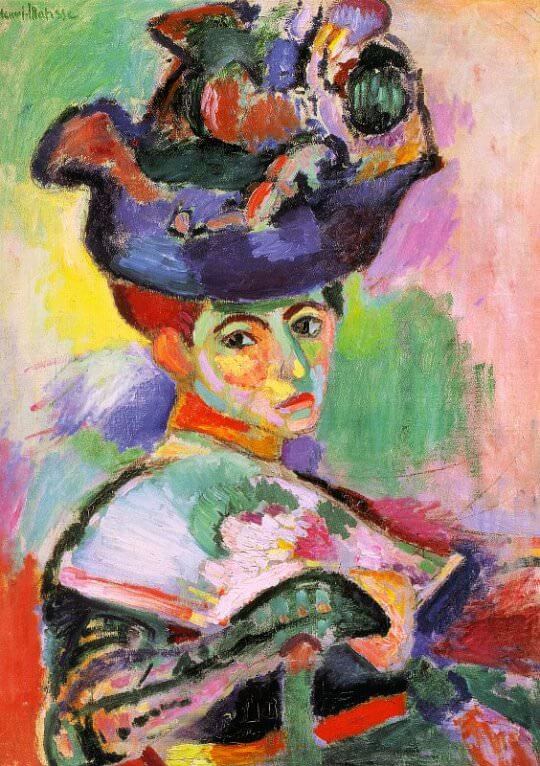

Woman with a Hat / Femme au Chapeau

Femme au chapeau marked a stylistic change from the regulated brushstrokes of Matisse’s earlier work to a more expressive individual style. His use of non-naturalistic colors and loose brushwork, which contributed to a sketchy or “unfinished” quality, seemed shocking to the viewers of the day.

The artist’s wife, Amélie, posed for this half-length portrait. She is depicted in an elaborate outfit with classic attributes of the French bourgeoisie: a gloved arm holding a fan and an elaborate hat perched atop her head. Her costume’s vibrant hues are purely expressive, however; when asked about the hue of the dress Madame Matisse was actually wearing when she posed for the portrait, the artist allegedly replied, “Black, of course.”

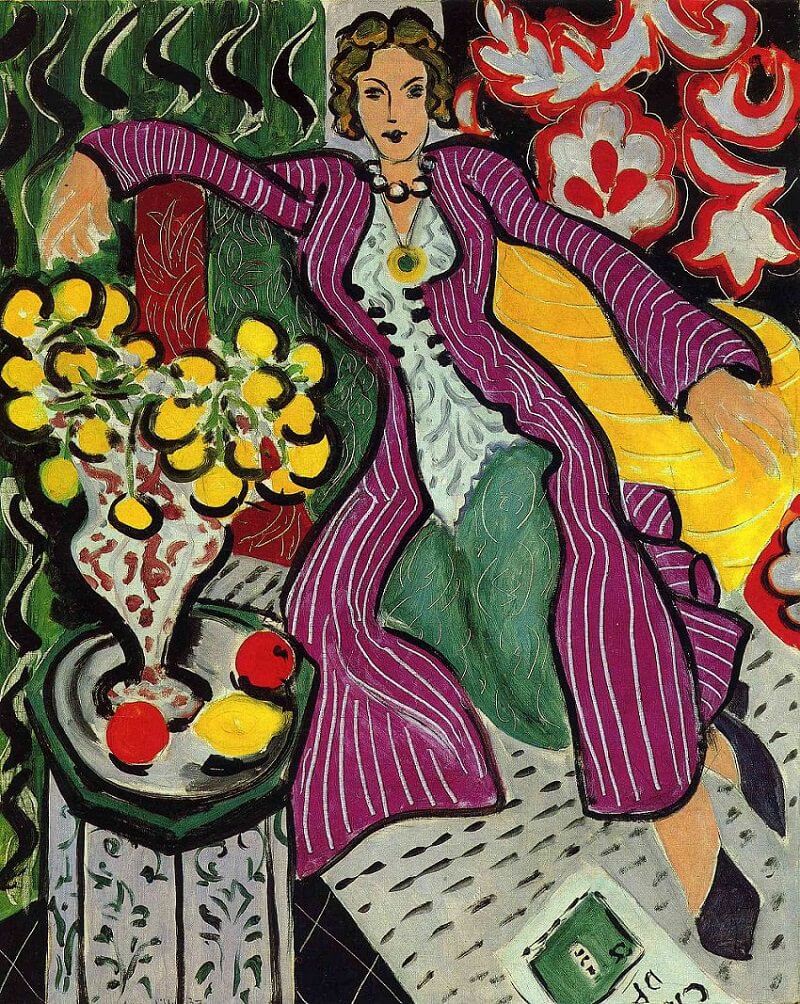

Woman in a purple coat

The Woman in a Purple Coat, 1937 is a superb example of the use of color and light to express his emotions in life, not towards his model like some artists, but to life itself. Although there is not a single straight line, the way the colors juxtapose each other there is no need for a straight line.

Everything else is surrounded by thick, black outline which accentuates all the other features, seemingly pushing out Lydia and all the other objects. The vivid, purple coat with the black outline makes Lydia almost pop out off the chaise lounge she is on, making her the main focal point, as she should be.

Photos Courtesy of Henri Matisse.org